The museum collection includes interesting objects that are today as unfamiliar and unrecognisable to the younger generation as a farthingale. Some of these items include a magic lantern, a cinema ice-cream seller’s tray and a large box of cinema lobby stills from film productions. One interesting item on display is a cardboard advertising ‘lion’. These items represent a magic age of entertainment when the cinema became a massive force in the community and brought colour and romance into everyday lives.

Now on display in the main gallery, this photograph of the Rex Cinema’s ‘Disney style’ lion was taken in the ruins of demolition prior to the removal of the object. Image 22/217 reproduced by kind permission from Rhondda Cynon Taf Libraries.

The Rex Cinema lion on display in the museum exhibition. Image by CVM.

The first moving pictures were seen in Paris in late December 1895. The experience was a sensation and the entertainment quickly spread around the world. At first, the showing of ‘movies’ was limited to Music Halls and Fair Grounds.

These ‘living pictures’ were first seen in Aberdare in September 1896. The Aberdare Times recorded; ‘the cinematographe, the electric photographic sensation showing animated pictures taken from real life which has been exhibited in Aberdare for the very first time and is a really marvellous invention. It need hardly be mentioned that it meets with unbounded applause.’

They were exhibited at the long-forgotten Empire Theatre, originally a circus arena, standing next to the Rock Brewery (Aberdare Times, September 19th, 1896).

The following year an audience watched animated pictures of Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee procession, shown by Harvard on his latest cinematoscope (Aberdare Times, November 6th, 1897).

The Empire Theatre. Detail from a photograph of the Rock Brewery. Image 13/b/002 reproduced by kind permission from Rhondda Cynon Taf Libraries.

The people of Aberdare had, of course, long enjoyed watching images projected by magic lanterns, the more sophisticated of which had an element of movement and had seen panoramas, dioramas, and myrioramas at local theatres, but this new form of amusement was far superior.

The Aberdare Times, 8th October 1864.

An artist would be sent to war zones to sketch the battles. On their return, they would paint the scenes in colour on huge canvasses. Transparencies, animation, and sound effects were added to provide realism. The scenes would be wound across the width of the stage and a narrator would relate the story in a dramatic fashion.

The opportunity to see moving pictures was limited, however, and fans had to wait for the visiting fairs, held twice a year, or itinerant showmen. The most famous of these was William Haggar.

‘Haggar screens the best, others screen the rest’ (Promotional slogan) William Haggar, Bioscope showman. Cartoon, Merthyr Express, 9th July, 1910.

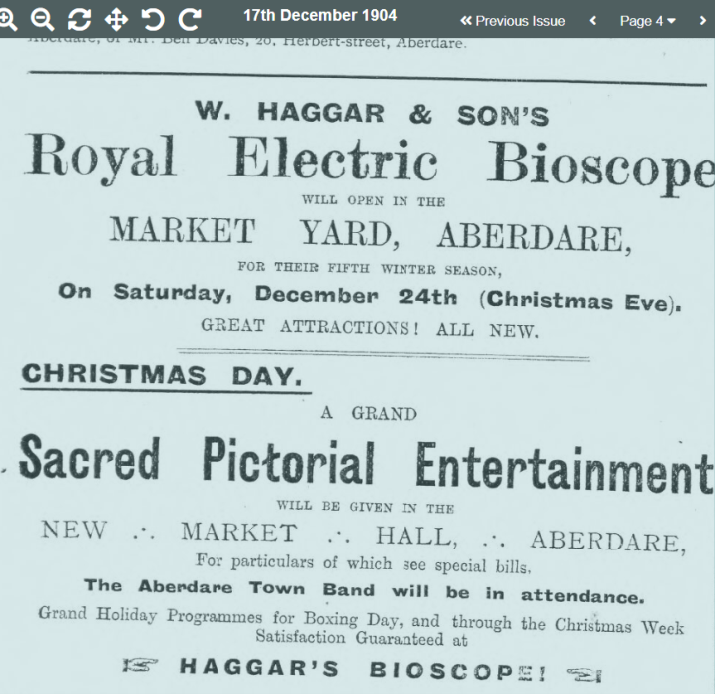

Haggar was a travelling showman who toured the industrial valleys of south Wales with his tented Bioscope shows, eventually settling in Aberdare and setting up his Royal Electric Bioscope and later his Coliseum in the Market Yard circa 1904, and opening a fine purpose-built cinema, the Kosy Kinema, in Market Street in August 1914. Reviewing one of his shows in 1913 at the Coliseum, The Leader said that; ‘We were astounded at the magnificent display of the latest and best pictures. Not only were the subjects beyond reproach but the quality was perfect. We had seen pictures at other places, [but Haggar’s] were without that objectionable flicker that ruins the eyesight. Of course, the show is not a Drury Lane one but it is now well fitted out and cosy’ (The Aberdare Leader, February 1913).

In his early days, Haggar also used the Market Hall as an auditorium. A memorial plaque has been placed on the exterior wall of this building commemorating his pioneering work.

The Aberdare Leader, 17th December 1904.

Haggar went on to make his own films, with family members as actors. He took an active role in the affairs of the town and served as a District Councillor. He named his house on Abernant Road, Kinema Villa.

The Haggar family at Kinema Villa, Abernant Road. Image 31/b/078 reproduced by kind permission from Rhondda Cynon Taf Libraries.

A young William Haggar behind his movie camera. (Aberdare Leader)

Haggar’s was not, however, Aberdare’s first cinema as that was The Aberdare Cinema, or Electric Theatre, in Cardiff Street which opened in 1912. It could seat 900 people.

The Aberdare, aka The Electric Cinema, was the town’s first custom-built cinema. After it closed it became the Cooperative Society’s food hall and a café was set out in the former balcony area. A postcard reproduced by kind permission of Mr. Gareth Thomas.

Uniformed messenger boy at the Aberdare Cinema: Philip Beronnell ca 1915. Image 22/226 reproduced by kind permission from Rhondda Cynon Taf Libraries.

The opening of Haggar’s Kosy Cinema, Market Street in 1914. The cinema was destroyed in a fire in the 1940s. Its shell still stands. It became a smart furniture showroom (Victor Freed) and is now occupied by a betting shop. Image 01/l/005 reproduced by kind permission from Rhondda Cynon Taf Libraries.

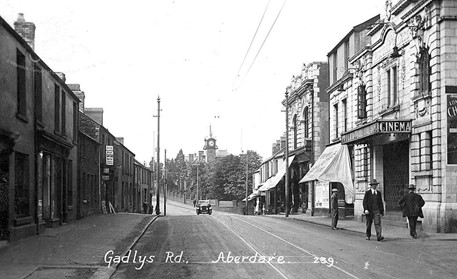

Thereafter, there was a cinema boom and the Park at Gadlys opened the same year as Haggar’s Kosy (1914). Every district would soon have its own picture house and some existing theatrical houses went over to movies. The Aberdare Empire (the second of that name), a bijou music hall within the Constitutional Hall, showed occasional pictures from 1910 becoming a cine-variety theatre.

Two cottages were demolished on St David’s Square, Cwmaman, to build a cinema. Erected on the site of 1 and 2 Amman Court and promoted by a Cardiff consortium, the cinema and billiards hall were in operation by March 1914. Pictures were also being shown at the Workmen’s Institute at that time.

Built ‘after the latest London style’ the art-deco Cwmaman Cinema (1914). Pen and ink drawing by the late Mr. John Jenkins of Cwmaman. Reproduced by kind permission of Mrs. Cheryl Dally.

The managers of these cinemas became well known local characters; William Haggar publicised himself as ‘Old Haggar’ and Louise S Clarke of the Aberdare Cinema as ‘Clarke’s the Man’ and ‘Clarke yw’r Dyn.’

In 1914 Clarke screened ‘sound films’, The Jew and In Peril of the Law, billed as the most expensive and marvellous attraction ever brought to Aberdare. This greatest wonder of the age was brought by Edison’s Kinetophone Talking Pictures. (Aberdare Leader, 23rd May 1914). This invention was short-lived as there were problems with synchronisation and projectionists were unable to cope with the technology. A decade was to pass before sound was reliable.

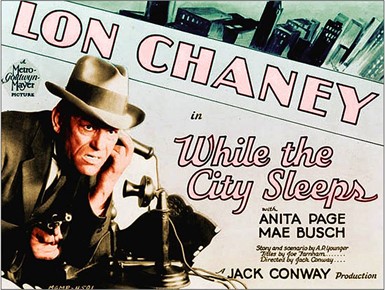

Gadlys Cinema, that week’s film (advert on pine-end) has been identified as While the City Sleeps released in 1928. It usually took some time before the big films reached small towns. The now shabby façade of this cinema still exists. (Postcard and image research courtesy, Mr Gareth Thomas)

The Temperance Hall, later called The New Theatre and Hippodrome, in 1918 was named The Palladium. It was modernised and given an art deco façade in the 1920s. There was The Palace Theatre, Hirwaun (originally The Victoria Hall) in 1910. Interestingly the Miners’ Welfare Halls, many of which had integral theatres, also converted to moving pictures whilst retaining facilities for live shows. One of the largest workingmen’s halls in the valley was the Aberaman Hall which leased its ‘Grand Theatre’ to the former Diorama operators, Poole, and which opened as Poole’s Picture Palace.

Left, the Aberaman Hall. Image GC1039 reproduced by kind permission from Rhondda Cynon Taf Libraries. Right, advertising card for Poole’s who leased to the hall to show pictures. Image by Geoffrey Evans.

Moses Freedman, an enterprising Mountain Ash Jewish businessman and a gramophone record dealer, started showing pictures at the Abercwmboi Workmen’s Hall and Institute in 1919.

Abercwmboi Hall. Image by Geoffrey Evans.

In 1924, sound was introduced, giving picture-goers a whole new perspective and experience.

The relatively small town of Mountain Ash maintained three cinemas, Haggar’s Palace (1910), The Empire (originally a variety theatre) and Nixon’s Workmen’s Hall (aka The New Theatre).

Haggar’s Palace, Oxford Street, Mountain Ash. The film advertised is Johnny, Get your Hair Cut starring Jackie Coogan. It was released in 1927. It was a silent film taking up 5 reels and running for 50 minutes. Image from a postcard, Geoffrey Evans collection.

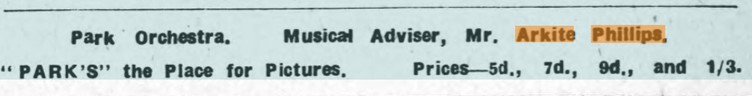

Prior to the introduction of sound, most local cinemas had their own small orchestra (those that didn’t would employ a pianist) which had to be skilled in improvisation as it was essential to compliment the changing mood of the film. Arkite Phillips, who had a music warehouse in Canon Street, and was the father of the late Peter Phillips MA (Pep), a senior teacher at Aberdare Boys Grammar School, was musical director of several local picture houses including the Park.

The Aberdare Leader, 16th August 1919, advert page 4.

The acme of cinema building in Aberdare was the splendid art deco Rex Cinema Aberdare which was opened on the 10th April 1939 by W E Willis and is named after his son Rex Willis (1924 – 2000) the Welsh International rugby union fly-half.

Left, The Rex. Right, Art Deco panel from the cinema’s interior. An exact copy can be seen at the Coliseum, Aberdare. Image 01/k/055 reproduced by kind permission from Rhondda Cynon Taf Libraries.

This luxurious cinema, one of the finest in South Wales, had seating for 1,250 people and was equipped with a Compton Theatrone organ which rose on a lift from below the stage, its glass console illuminated with constantly changing coloured neon lights. A selection of classical and popular music was played during the interval by the organist who was immaculately turned out in white tie and tails.

The Park Cinema introduced children’s morning matinees in 1914; ‘Send your children to our matinee at 11. 00 o’clock and Mr Hopcroft [the manager] will personally look well after them. Park’s the Place!’ In the 1950s and 60s children’s Saturday morning matinees became popular with specially selected films and serials; Cinema Clubs evolved from these performances. The Palladium hosted a popular children’s association. In the ‘serials’, each episode had a ‘cliff-hanger’ ending, which were especially popular; memorable titles included The Perils of Pauline, Kit Carson and Flash Gordon. Improved cinema technology brought innovations such as Eastman colour, Technicolour, Tod-AO, CinemaScope (1953 – 1967) and Cinerama with their wide curved screens.

In its decline the cinema alternated films with bingo sessions; it finally closed its doors in July 1983. It stood derelict for some years and was, ironically, used as a location for the Welsh language film, Coming up Roses, in which a fictitious village cinema is used as a mushroom farm. It was demolished in 1990 and is now one of the town’s car parks. And yet, on its opening day, people queued for hours for a seat, and it continued to be ‘the venue’ for picture-goers for a long time.

Smoking was permitted in all the local cinemas and many will remember the pinpoints of glowing cigarette ends in the darkness and the plumes of airborne cigarette smoke swirling in the beam of the projector. Nevertheless, it was a great social occasion to visit the cinema (films sometimes changed mid-week) and look out across the auditorium for friends and acquaintances during the interval and wait for them in the foyer at the end of the show.

Television was responsible for the decline of the cinema from the mid-1950s; many alternated Bingo sessions with film screenings but to no avail. Slowly they closed and the buildings were put to other uses. The Aberdare Cinema became a grocery outlet and Park Cinema became a garage and a tyre depot. The Grand at Aberaman reverted to a venue for the local amateur operatic societies, until these, too, folded. Other buildings became derelict.

Written by volunteer, Geoffrey Evans, March 2021.

Notes, Sources, and Further reading:

From 1903 onwards the Aberdare Leader abounds with bioscope and cinema references; these entertainments were significant in the community, and columns are given up to new cinema openings, advertisements of forthcoming attractions, reviews of films, and general information. Interesting sidelights are the struggle for Sunday performances, the antipathy to this new entertainment by some local non-conformists ministers, particularly the Rev Cynog Williams of Heolyfelin Chapel (see ‘Works of Darkness’ Aberdare Leader, August 1, 1914), and the friendly rivalry between local cinemas. These topics are outside the scope of this general article.

Select references are included in the above text and the following sources give the dates of the earliest known existence of bioscope shows, and the opening of the principal Aberdare Valley cinemas.

- Harvard’s Cinematographe, Aberdare Times.19 September, 1896.

- W Haggar & Sons, Royal Electric Bioscope, Aberdare Leader, (hereafter AL), January 10, 1903.

- Haggar’s Bioscope Co. Aberdare Leader, 12 February, 1910

- Haggar’s Bioscope, Aberdare Leader, 17, September, 1910.

- Haggar’s Coliseum, Aberdare Leader, 22 March, 1913.

- Victoria Hall, Hirwain (later the Palace Cinema), Aberdare Leader 26 April 1913.

- Haggar’s, Mountain Ash. The building was completed by October 1912, Aberdare Leader, July 26, 1913.

- Aberdare Cinema, AL, October 6, 1913. Introduction of ‘Talking Pictures’ at the Aberdare Cinema, Aberdare Leader, 23, May 1913.

- Park Cinema, Aberdare Leader, March 26th, 1914.

- Cwmaman, Aberdare Leader, 18 July, 1914.

- The Empire, Mountain Ash, Aberdare Leader, 28 June, 1915.

- Kosy Kinema, Market Street, Aberdare, Aberdare Leader, 28 August, 1915.

- Palladium and Hippodrome, Aberdare Leader, 30 March and 22 June, 1918.

- Abercwmboi, Aberdare Leader, 30 August, and 6 September. 1919

- Rex Super Cinema. Opened 10, April, 1939, Aberdare Leader, 15 April. 1939

- Note: The Workmen’s Halls of an earlier period, most of which had integral theatres, also started showing pictures during the above period.

- Rhondda Cynon Taf Libraries Digital Archives, https://archive.rctcbc.gov.uk/home?WINID=1626176342179

- The National Library of Wales, Welsh Newspapers Online, https://newspapers.library.wales/

- Peter Yorke, 2011. ‘William Haggar Fairground Film-maker: Biography of a pioneer of the cinema’

- Rhondda Cynon Taf Library Services, 2018. Stephen J Dutfield, ‘Our Past – The Rex Compton Theatrone’ http://webapps.rctcbc.gov.uk/heritagetrail/english/cynon/rexcomptonorgan.html

- Rhondda Cynon Taf Library Services, 2018. ‘Our Past – William Haggar: Film Pioneer’ http://webapps.rctcbc.gov.uk/heritagetrail/english/cynon/haggar.html

-

[…] work from his time as a volunteer at Cynon Valley Museum. Jewish Heritage in the Cynon Valley Memories of the Silver Screen The Mountain Ash Choir: Hands Across the Ocean The Festival of Britain 1951 in the Valleys […]

Leave a Comment

Excellent article. I well remember the Saturday morning matinees in Cwmaman Workmen`s Hall, which would be full to the rafters with the village`s children. Incidentally, the so-called Palace Cinema, also in Cwmaman, was known locally, and unkindly, as the Bug House! Well done, Geoff

Thank you for this excellent article. I spent many happy times there in the 50’s. The Rex was a superb piece of late Deco and those interior panels were exceptional pieces of art. I look forward to seeing them again some time.

My uncle, Gurnos Griffiths, was the projectionist at the Rex, and I remember as a small child, eating ice-cream with him him on the roof.

What a delightful trip down memory lane! This article beautifully captures the rich history of cinema in the Cynon Valley. It’s fascinating to learn about the early theaters and the joy they brought to the community. The stories from local residents add a personal touch and show the impact that cinema had on their lives. Thank you to the Cynon Valley Museum for preserving this important part of our heritage. Jeanne Day