This blog will focus on an item in our collection used for industrial action, particularly the miners’ strike of 1985/85. The Penrhiwceiber Colliery Lodge banner beholds the story of a group of militant pit workers supporting the National Union of Miners (South Wales Area).

Image by CVM. The Penrhiwceiber Colliery Lodge banner in the main museum gallery.

The national context

During the 1980s, the British coal industry was known as the most efficient globally. However, the Conservative government began the process of privatisation, in which former state-run industries, such as gas and railway, were transferred to private sector ownership [1]. Their aim was to ‘slim down’ unprofitable businesses and create more efficient industries. It was also said that Margaret Thatcher wanted to weaken the trade unions because she believed they had become too powerful [1].

This encouraged sour relations between the government and the National Union (N.U.M.). Furthermore, in 1983, Thatcher appointed Ian MacGregor as the head of the National Coal Board. MacGregor’s background was in British Steel, in which he had a reputation for cutbacks and closures [2].

Tensions were rising in the NUM and resolutions were passed promising that pits would strike if they were to be closed for reasons outside of geological or resource exhaustion [2].

On 1 March 1984, The National Coal Board announced its plans to close 20 coal mines, resulting in a loss of 20,000 jobs. Locally organised strikes across the UK resulted in a national NUM strike [1].

This was considered a calculated decision by the government, as it was later revealed that they had prepared for the event and subsequent industrial action, by stockpiling coal to take Britain through the winter [2].

Mineworkers in South Wales

The South Wales Area of the National Union of Mineworkers was known to look after its members. In the early 1980s, they had high membership numbers and strong links to the Labour Party [2].

____________________________________________________________

“The miners in south Wales are saying – we are not accepting the dereliction of our mining valleys, we are not allowing our children to go immediately from school into the dole queue – it is time we fought!”

Emlyn Williams, President, NUM, South Wales Area [1] ____________________________________________________________

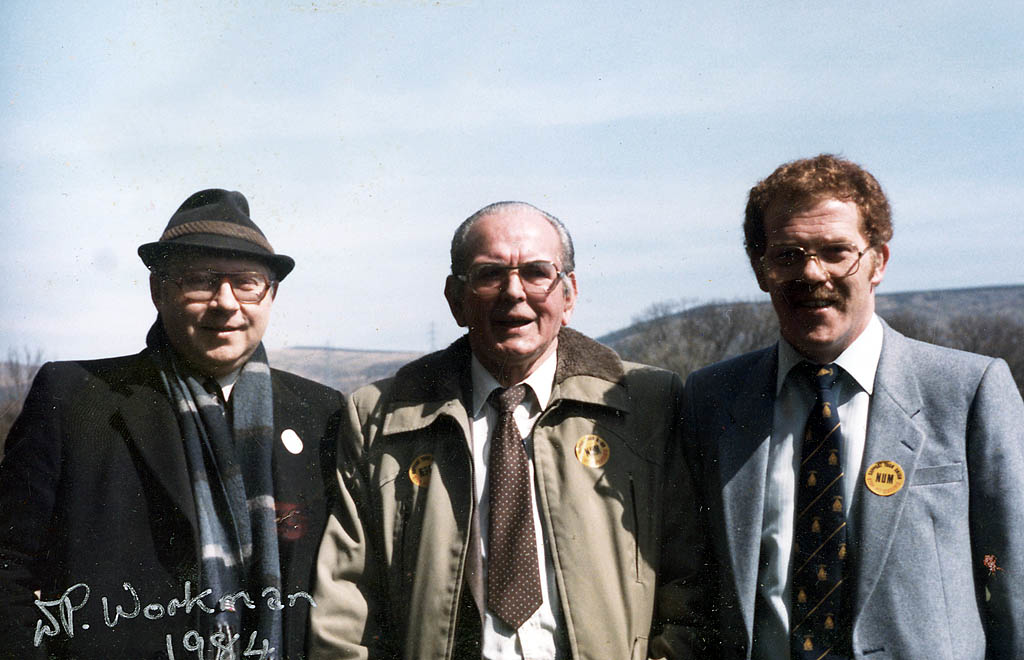

Image 05/b/k/131 Miner’s Strike rally at the Ynys Fields, 1984

Left to Right: Tom Hanley (Seamen); E M Williams (N.U.M.); Derek Gregory (NUPE). Image reproduced by kind permission from Rhondda Cynon Taf Libraries.

The commotion and anger leading up to the 1984 strike were not new to mineworkers of Wales. Similar conflicts over industrial action occurred in the 1960s and 70s but also date even further back to the ‘Tonypandy Riots’ of 1911 (image below).

Image 24977 Miners marching to Pontypridd to attend the trials of the “Tonypandy Rioters”, 22nd February 1911. Image reproduced by kind permission from Rhondda Cynon Taf Libraries.

The issues in the 1980s were also teamed with dangerously high unemployment. The future of the coal mining industry was threatened. In 1982, only 62 apprentices started worked in south Wales, despite 1,400 applicants showing interest. This was a dangerous state to be in as many believed the ‘future of your pit is your young people. If you don’t train your young people, you’ve had it’ [3].

With so many men out of work in an area which was almost single-industry, there was a high result in deprivation and breakdown in the community [2].

Interestingly, the support for industrial action in the 1980s differed in Wales between the north and south. In the north, only 35% of 1,000 men employed went on strike [2]. In south Wales, although the statistic fluctuated over time, once the strike was established the support remained at 100% until November 1984. The difference in landscape and the higher number of farmers and land workers in the north could be accounted for in this difference. Whereas the south had a higher number of collieries and deep mines which resulted in great alliance with and support for the NUM and the miners’ cause.

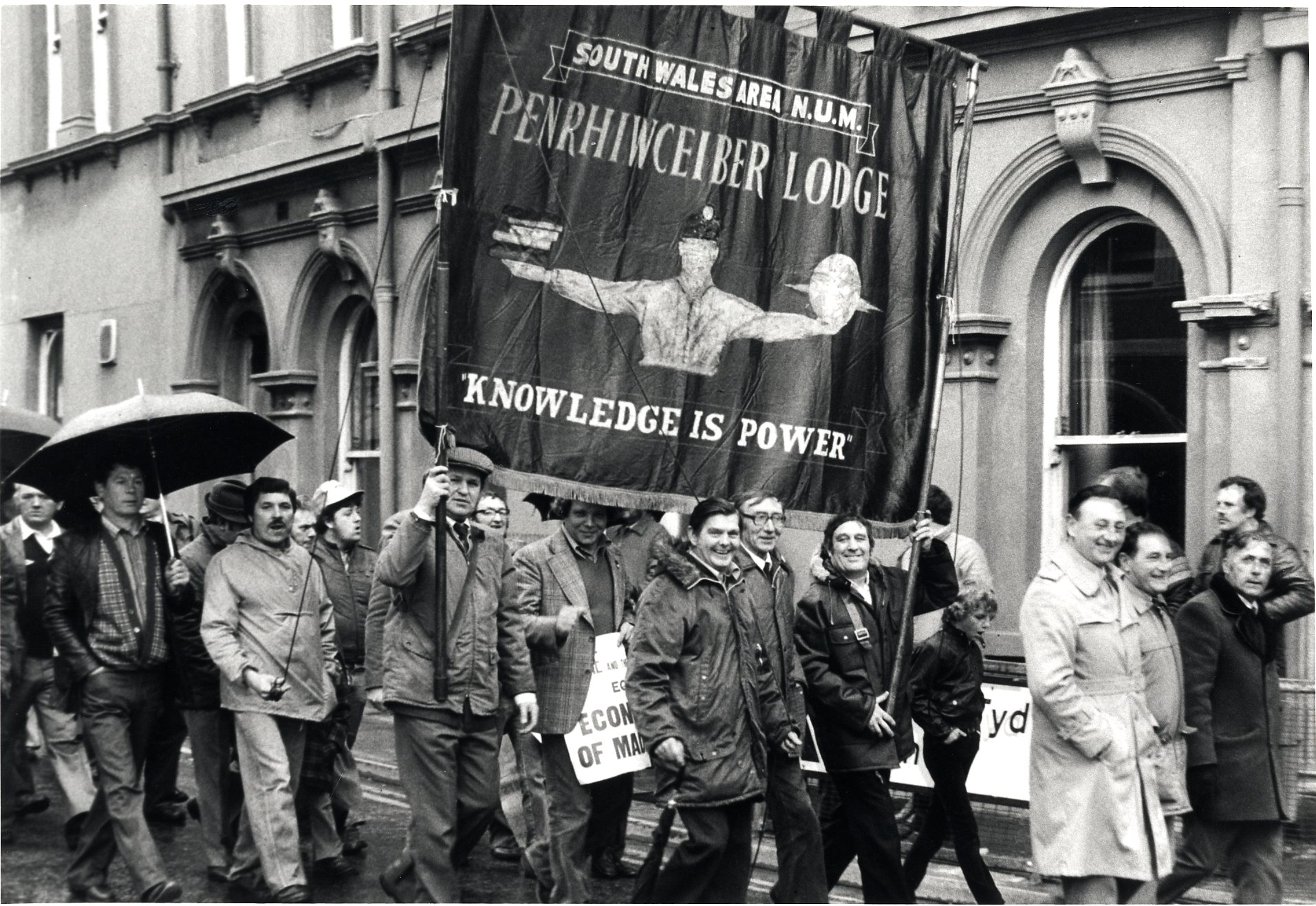

In journalist Alex Mitchell’s memoir ‘Come The Revolution’, he explains that the Cynon Valley was given the title ‘Scargill Valley’ after Arthur Scargill, the President of the NUM (1982 – 2002) [4, page 446]. Images from the Rhondda Cynon Taf Digital Archive show the Penrhiwceiber Colliery banner being used in a large parade on June 16th 1984, the day that Arthur Scargill visited Treorchy.

Image 2516: A march through Treorchy for Arthur Scargill’s visit to the Rhondda, June 16th, 1984. Image reproduced by kind permission from Rhondda Cynon Taf Libraries.

The Penrhiwceiber Colliery Lodge

Each coal pit had a lodge or branch which operated as the basic unit of local organisation. The lodge represented its men and would lobby on their behalf at a local level [5]. The colliery lodges were considered as part of the essential foundation for the overall strength of the south Wales N.U.M. [3]. They also helped to develop social and cultural organisations that benefitted the whole community [6]. For example, in 1888 the collieries helped build the Penrhiwceiber Workmen’s Hall and Institute [7].

Many lodge leaders had great influence. Mike Griffin was a well-established leader of the Penrhiwceiber Colliery lodge. He acted as the Secretary throughout the 1970s and 80s. He was described as ‘a good orator… and a genuine trade unionist who fought hard for what he believed.’ He was also a committed Labour Party member [3].

ACVMS 2000.444 The Penrhiwceiber Lodge N.U.M on march in London, 1984.

This striking banner was commissioned by the Penrhiwceiber Colliery Lodge in the 1960s, replicating symbolism used in a previous banner for the Mountain Ash & Penrhiwceiber Lodges. The banner reads ‘South Wales Area N. U. M., Penrhiwceiber Lodge’ ‘Knowledge is Power’ and has the image of a miner holding a pile of books in one outstretched hand and a world on its axis in the other outstretched hand. This symbolism was also used on pin badges and posters. The banner was used in many strikes and it is likely that the banner was used in marches outside of south Wales, traveling further afield to places such as London.

Image by CVM.

ACVMS 2000.428 The Penrhiwceiber Lodge banner being used on a march, date unknown.

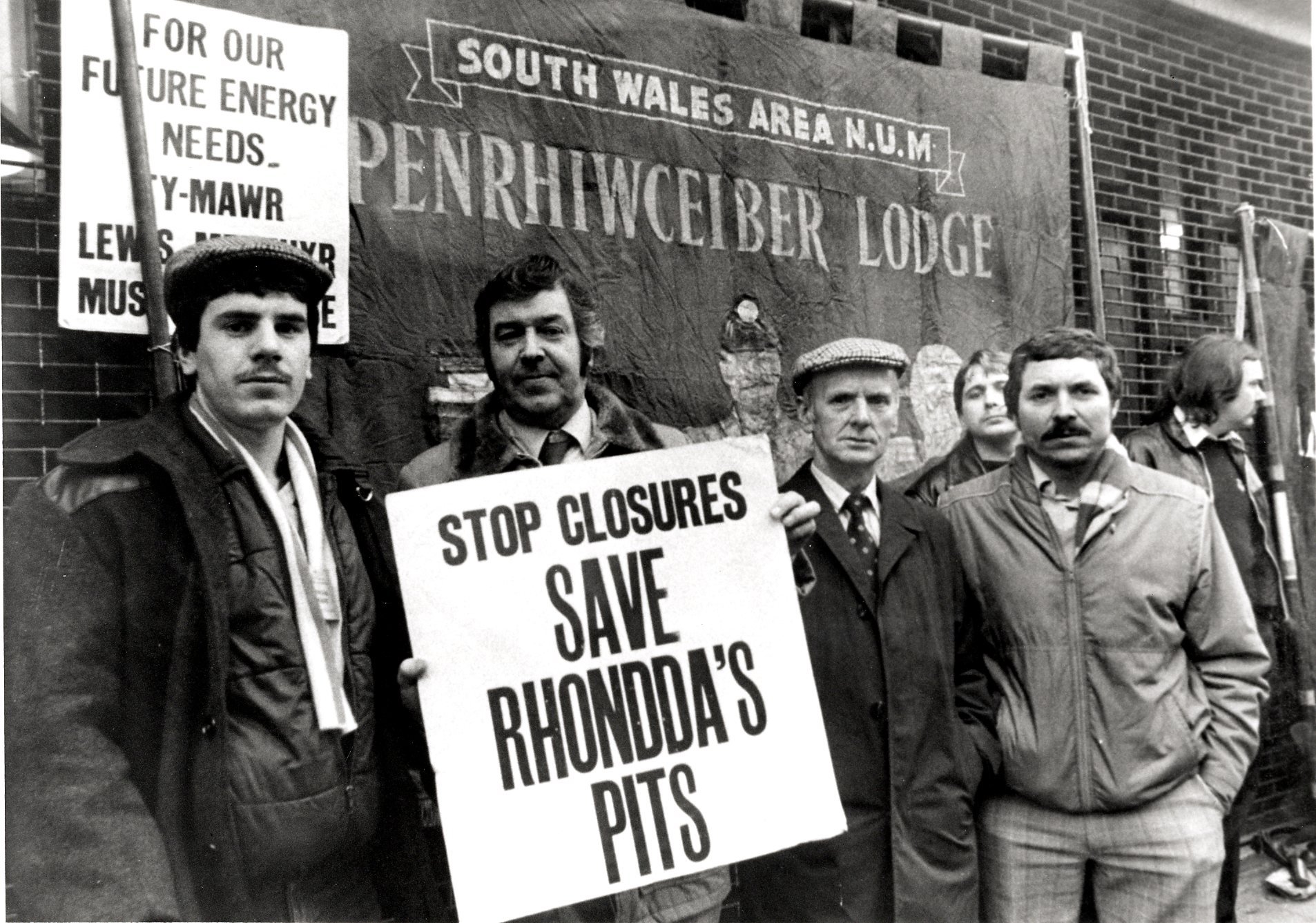

The Penrhiwceiber Colliery Lodge were known as ‘militant activists’ as they showed great resilience and support for the miners’ cause. During the 1983 Lewis Merthyr Colliery strike, 94% of the Lodge Union voted in support of the strike, including the Penrhiwceiber Lodge [3].

Similarly, during the 1984/5 strike, it was recorded that about 93% of the South Wales Area members stayed on strike for the duration of the year-long dispute, and Penrhiwceiber was one of the lodges that remained 100% on strike until the end [3].

ACVMS 2000.427 The Penrhiwceiber Lodge banner being propped up against a wall while people protest with ‘Save Rhondda’s Pits’ signs. It seems there is a different colliery group by their side, as another banner can be seen in the left corner of the image.

Image mt/16/009: Demonstration at Penrhiwceiber Colliery during the Miner’s Strike, 1984. Image reproduced by kind permission from Rhondda Cynon Taf Libraries.

Their militant action would have greatly impacted their community in many ways. Although there were would have been a sense of purpose and community, fighting for what they believed in, there was also great despair and deprivation. In many areas, community food banks were created, heavily organised by the miners’ wives and particularly supplying the families of miners, who had not received support or income throughout the year of the strike [1]. In some areas, people would dig for coal in local tips for their own personal use (images below).

Image mt/05/a/b/034 (left) and Image mt/05/a/b/ 028 Collecting coal at Cwmcynon Tip during the Miner’s Strike, 1984-1985, Penrhiwceiber. Images reproduced by kind permission from Rhondda Cynon Taf Libraries.

Decline in coal Industry

The strike action had stopped by March 1985, a year after it had started. The end of the strike was sparked by exhaustion of the miners, hunger and unemployment, and negative involvement of the media [6]. On 3 March 1985, miners walked to their pits back into work, with their posters and banners still held high [6].

Sadly, the National Coal Board continued with their plans to close the pits they deemed as inefficient and uneconomic [6]. A significant consequence was the gradual pit closures across south Wales, including Penrhiwceiber which closed on 8th October 1985 [3]. In 1984, there were approximately 20,000 miners in Wales; however, there were only 3,700 by the end of the decade [6].

By 1994, the coal industry had been privatised [2].

Sources:

[1] National Museum Wales online., (2019). The Miners’ Strike of 1984, [Accessed January 20th 2021], Available from: https://museum.wales/articles/2009-03-12/The-Miners-Strike-of-1984/ [2] BBC Online Wales History., (2008). The Miners’ Strike, [Accessed January 20th 2021], Available from: https://www.bbc.co.uk/wales/history/sites/themes/society/industry_coal06.shtml [3] Curtis, B., (2013). The South Wales Miners 1964–1985 (Cardiff: University of Wales Press). [4] Mitchell, A., (2011). Come The Revolution: A Memoir, Sydney: NewSouth Publishing [5] Swansea University Special Collection, Coalfield Web Materials ‘National Union of Mineworkers’, [Accessed January 20th 2021], Available from: http://www.agor.org.uk/cwm/themes/Life/society/unions/national_union_of_mineworkers.asp [6] National Museum Wales. Pickets, Police, Politics, [Accessed January 20th 2021], Available from: https://museum.wales/media/9753/strike-en.pdf [7] British Listing Buildings, Penrhiwceiber Institute and Community Hall, [Accessed January 21st 2021] Available from: https://britishlistedbuildings.co.uk/300080942-penrhiwceiber-institute-and-community-hall-penrhiwceiber#.YDUWM-j7Q2w [8] Mining Heritage, Union Banners, [Accessed 25th January 2021], Available from: https://miningheritage.co.uk/union-banner/Rhondda Cynon Taf, Library Service Digital Archive, [Accessed January 20th 2021] Available from: https://archive.rctcbc.gov.uk/home?WINID=1614094706145

Further reading:

University of Wolverhampton, On Behalf of the People: Work, Community and Class in the British Coal Industry 1947-1994, [Accessed 9th March 2021] Available from: https://www.coalandcommunity.org.uk/tower