Image produced and owned by Cynon Valley Museum.

The museum has safety lamps on display with miners’ tags and other equipment. Only equipment to the layman, but essential and lifesaving to miners who see these artifices as symbols of the bond they shared in their former employment which they would never forget.

The safety lamps produced by E. Thomas & Williams started as a local product but were soon exported to countries across the world.

The Start of Coal Mining

Early man started to settle in areas which seemed suitable; forests with water nearby and mild climate if possible from 4000BC onwards.

Coal which was found near the surface and on outcrops from hills meant that fire could be used as a medium for making tools and useful items. This is known for certain, as late Stone Age and Bronze Age axes have been found very near the surface of exposed coal seams. The Romans started mining on a small scale, shallow pits by following seams into hills. Copper, lead, tin, and even some gold were gradually extracted when possible as these minerals are useful.

Early Technology

In time, early technology improved to allow exploration further and deeper into the earth. The main method was to follow the outcrop (where a large amount of coal surfaced) and remove the coal until opening a cave or tunnel. As the mine went deeper, there was a need for two things: ventilation and light. The answer for both was naked flames, a fire set in the mine drew air in from the outside, and candles were used for light, however, this created a serious problem in coal mines.

With coal, there is always the presence of highly explosive methane which explodes if near a naked flame, with disastrous results. The deeper the mine the more methane is present. The only way available was by using a “fireman”, this individual would cover himself in wet rags and go down to the coal face at the start of a shift. He would carry a candle on the end of a long stick. holding it up high towards the roof. The idea was to set off the methane which would mean that for a time there was no methane in that area. The fireman would have no idea how much methane was present so he risked death every time.

The ventilation problem was eased in the 1750s. The steam engine-powered pumps forced air into the mine but did not help with methane production. The industrial revolution demanded a continuous coal supply which led to more injuries and death. Up to this point, all coal mining underground was carried out with the uncertainty that every shift you were risking injury or death from the danger that could not be seen or warned of.

A crude form of testing using an open flame lamp which was carried into the working area at ground level. As the tester carefully walked on he raised the height of the flame keeping a close watch on the colour of the flame. If the tip of the flame did not change colour as the flame was raised higher the area was safe for now. If, however, the colour changed to a bluish grey and then to a deep blue, firedamp was present. The candle was lowered and arrangements were made for the ventilating of the area or the deliberate firing of the gas at the end of the shift.

This method was still being used in the 1800s when pumps were available in the big mines to clear the atmosphere. The miners had no choice but to do this every day until real efforts were made to produce a safety lamp.

Impacts of The Industrial Revolution

It was now that scientists applied themselves to a solution. This was the age of enlightenment and the industrial revolution, a time when there was a zest to improve and try anything to achieve a result for the better. Many scientists and industrialists did not concentrate on one particular “field” but became involved in several areas. There was much encouragement from parliament, the Royal Family, and the Royal Societies for the Arts and Sciences. An example, steam locomotive pioneer George Stephenson produced a working example of a safety lamp while designing locomotive and rolling stock.

Item 2008.108/10: Classic Stephenson lamp with glass tube inside gauze. Source: National Museum Wales

Some weird and wonderful ideas were tried, fish skins for their luminous properties, bottles of fireflies, a spinning disk with a flint creating a shower of sparks, this was of course totally dangerous as it would ignite any methane gas or damp for certain.

Fire needs air and fuel to burn, whilst fuel could be supplied within the lamp, the air is always present. The prime requirement for success is for the flame to produce light without igniting any explosive gases present.

The scientists knew from other experiments that flames cannot escape through metal gauze, but the size of the holes had to be big enough to provide light but small enough to stop flames from escaping through the holes. William Clanny made a lamp that used bellows to pump air through water to a candle enclosed in a glass cylinder, this was very clumsy and gave out a weak light.

George Stephenson produced a lamp that used a tall chimney but again the light was not very strong. The next model did use gauze but also tended to be fragile. Sir Humphrey Dave produced a lamp that was used quite a lot. It made use of gauze. The size of the holes was arrived at after many experiments at his home laboratory. The correct size of holes, apart from giving light, detected the presence of firedamp as the flame burnt a lot brighter. All the outer casings of each lamp were made of brass or tinned steel, and those made of iron could have caused a spark with fatal consequences.

Item 27.443/1: Flame safety lamp, Davy type. Source: National Museum Wales.

It was an improved model made by William Clanny in 1816 using the best aspects of Davy’s and Stephenson’s lamps that earned him a gold medal from the Royal Society. It was also more serviceable than all previous lamps. Clanny mark two was the type on which all the later flame lamps were based.

Item 58.279/1: Clanny flame safety lamp with gauze top, used in mines 1860-1880. Source: National Museum Wales

Although the safety lamps did save lives they were not the complete answer. The light would never be as good as the first electric lamp which was invented in 1859. They were improved over the years and lighting systems were later installed in the main areas of mines. Safety lamps could still be damaged by dropping or hitting, and a flame could “leak-out” and cause an explosion. For example, in Wallsend, 1818, when 4 men were killed. If a safety lamp went out the miner was required to return to the bottom of the shaft to relight it. Lamps were locked to prevent relighting at the face and the tool to open them was kept at the bottom of the main shaft. These lamps were called protector lamps, the flame was provided by oil.

These safety lamps must have felt a lot better to use for the miners who used candles before. Only those who have worked in a deep mine can understand the difficulties of working in the heat, cramped space, and darkness. At least the protector lamps, once reliable, took some of the worries about fire and ever-present explosion. But the danger was always near; roof collapses, flooding, pit props breaking, runaway drams, and a host of other events.

The lamps were maintained by the skilled men in the lamp room who were charged with making sure the lamps were always in good order. The lamp room was used as a check to make sure all those miners who were due to surface did so. At the start of shift, each miner gave in his tally with his number on it to the lamp room in exchange for a lamp and at the end, they had to return the lamp and get their tally disc back.

Safety Lamp Production in Aberdare

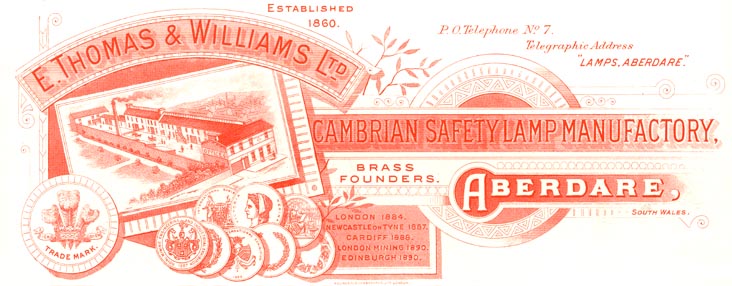

Evan Thomas was an ironmonger, inventor, and the original proprietor of Cambrian Lamp Works Aberdare, founded in 1860. The company initally presided at Cardiff Street, Aberdare, but moved to Craig Street in 1877. In 1907, the company established it’s now infamous name E. Thomas & Williams Ltd.

Thomas patented improvements to the Clanny lamp included making the glass lens more secure and also to allow any type of mineral oil to power it.

The No.7 as it was called was very successful and was recommended for universal use in all mines by the Royal Commission on Accidents in Mines. John Davis of Ferndale and a Mr. Williams joined Evan Thomas as partners in 1880.

During the 1890s the firm won many prestigious awards at industrial exhibitions including the gold medal at the London Mining Exhibition. This firm made working safety lamps mostly electric until the last of the mines closed. I say mostly because the oil power lamps are still seen as an essential tool for detecting dangerous gases in other coal mines abroad, ship holds, and sewers. As the coal industry expanded, E. Thomas & Williams products were exported worldwide!

ACVMS 1996.260_001. Image produced and owned by Cynon Valley Museum.

ACVMS 1996.260_002. Image produced and owned by Cynon Valley Museum.

Image reproduced with kind permission by RCT Library and Archive Services.

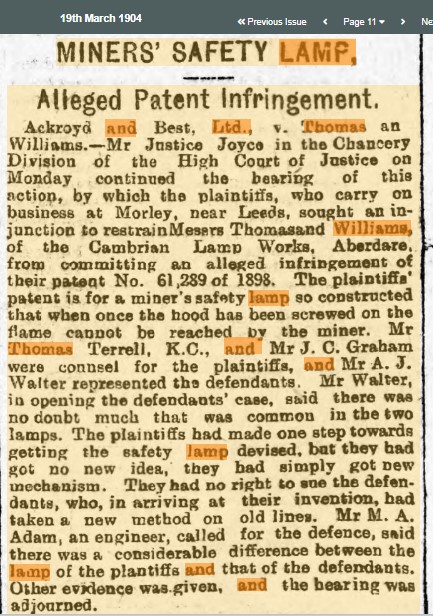

In the early 1900s, the firm was accused of patent infringement by Ackroyd and Best Ltd of Morley. They accused Thomas and Williams of the infringement of their ‘patent No. 61289 of 1898’ which allowed lamps to be constructed so that a hood was screwed to avoid the flame being touched. The plaintiffs were not charged as evidence showed ‘considerable differences’ between the lamps and that there was no base to ‘sue the defendants, who, in arriving at their invention had taken a new method on old lines’

The Cardiff Times, 19th March 1904, page 11. Source: Newspapers Online, The National Library of Wales.

The company contributed to the war efforts of both WWI and WWII. After a fire on premises in 1978, the company moved to a factory in Robertstown, where it is still trading today. The firm makes replica lamps that have been used in recent years as gifts /objects presented to retirees, union awards, and health and safety awards. This firm is recognised as being the oldest surviving safety lamp manufacturer still trading. Safety lamps of all types are collectibles and can command quite high prices.

Blog post written by volunteer Robert Glare.

Sources:

Adam Cresswell, 20 May 2020, ‘The history and Development of Mining in UK’, Available: https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/1765ca24ceae4dd6ad91682bf870fdac

Andrew Watson, 22nd November 2016, ‘Miners Lamp History from flame to Davy lamp to electric’ Available: https://www.hsimagazine.com/article/miners-lamp-history-from-flame-to-the-davy-lamp-to-electric/

Cynon Valley History Society, ‘A CHRONOLOGY OF THE HISTORY OF THE CYNON VALLEY TO c.2013’ Available: http://www.cvhs.org.uk/timeline/chron.html

Eric Edwards, Collections Pitt Rivers Museum, ‘England: The Other Within – Analysing the English Collections at the Pitt Rivers Museum’, Available: https://england.prm.ox.ac.uk/englishness-Miners-lamp.html

National Museum of Mining ‘Celebrating 200 Years of the Flame Safety Lamp’, Available: https://nationalminingmuseum.com/collection/projects/celebrating-200-years-of-the-flame-safety-lamp/

National Museum Wales Collections Online, Available: https://museum.wales/collections/online/

Rhonnda Cynon Taff Library Service, Available: https://archive.rctcbc.gov.uk/home

Rhondda Cynon Taff Library Service, ‘Our Past -ABERDARE – CAMBRIAN LAMP WORKS – E. THOMAS & WILLIAMS’ Available: http://webapps.rctcbc.gov.uk/heritagetrail/english/cynon/aberdare-lampworks.html

Wikipedia, ‘Safety Lamp’, Available: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Safety_lamp