Exhibition at Home

The Healing Hand of Nature

Roy Carr

The Power of Being in the Natural World

By Roy Carr

“Have you been to Pits Woods yet?” Annabelle asked.

“No, where is it?”

“Up by the ‘old age’ and through the park”

I didn’t recognise where she meant, and, feeling slightly embarrassed about my ignorance, I didn’t ask.

But there was something in that conversation which registered. She had described a beech wood, animatedly telling me how beautiful it was. I squirrelled away this kernel of knowledge, leaving it dormant in my head for some future forage.

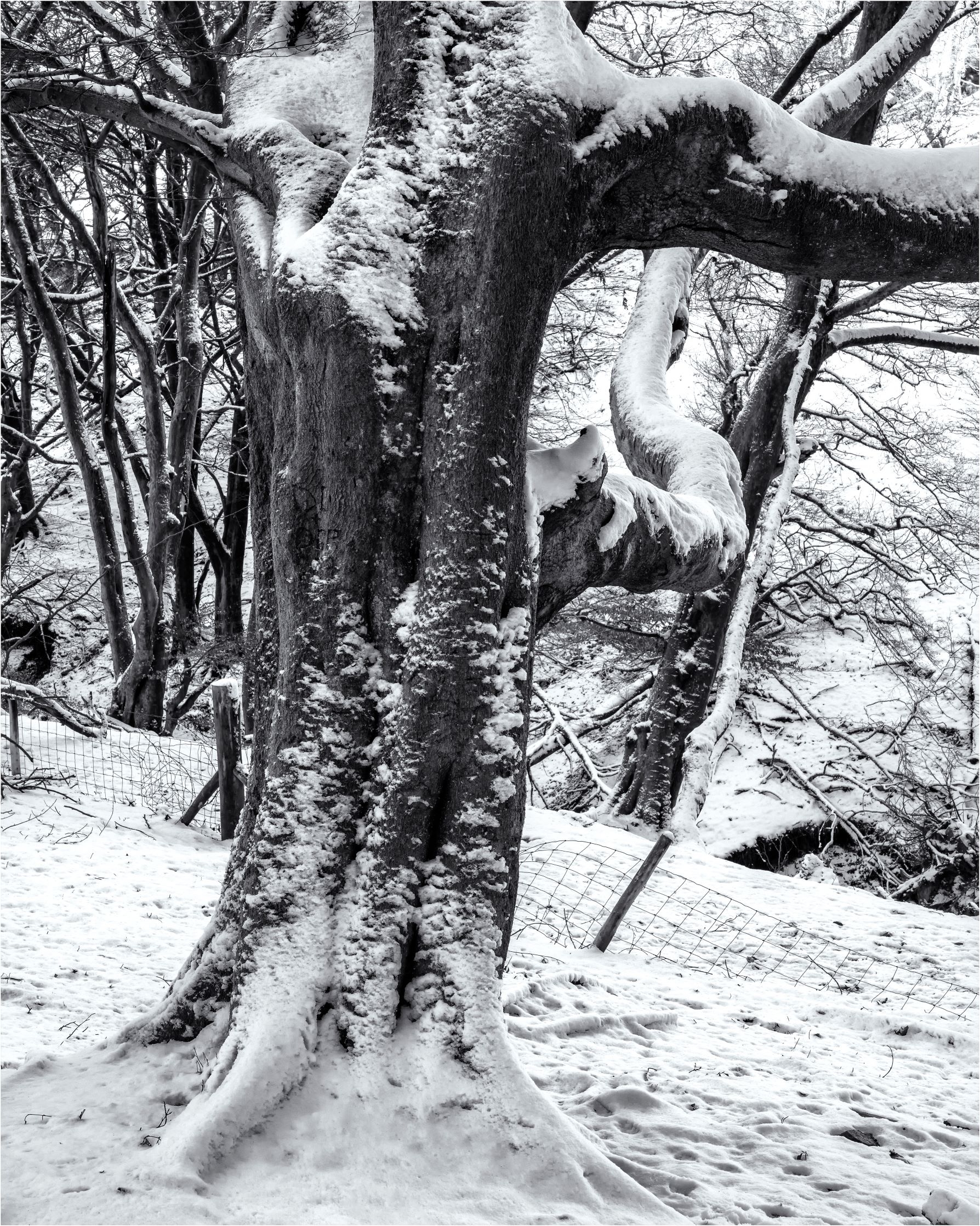

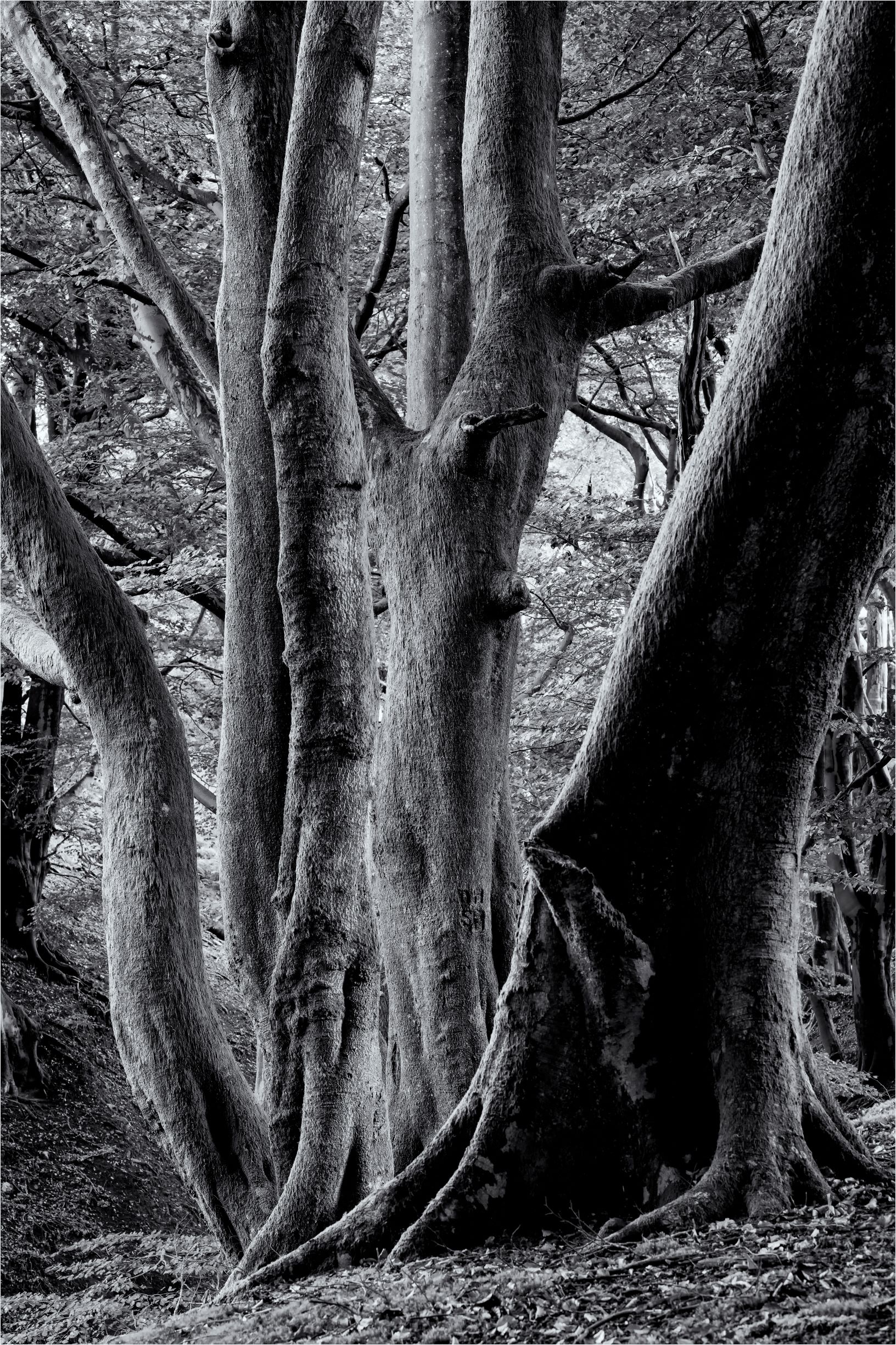

Bedlinog, the small Welsh village in south Wales where I live, is surrounded mainly by oak woods, twisting away through the mist in autumn. These are interspersed with birch, and ash, and alder. They are splendid, but the thought of a beech wood lingered. In my last home, on the edge of the Vale of Glamorgan, my daily dog walk took me past an enormous beech, four hugs in diameter, which cast a spell on me. She invited me to hunt for her beech neighbours which I found with relish, and each of them left their mark as I discovered their particular magic: the vivid greens of spring; the golden oranges of autumn; their sentinel appearance in winter and the breathing of life in summer. There, the thick blanket of leaf mould fed first the delicate wood anemones beneath them, and then the wild garlic which grew outside the shade of their canopy, injecting a different green into the wood and a scent which made me hungry.

Four weeks later, on an impulse, I went in search of Pits Woods.

Full of anger and distress my head jangled. The night before I read through a letter from a Psychiatrist about my brother who, just two weeks earlier, had taken his life. The letter, as previous ones, failed in so many ways, fanning my flames of despair. I struggled to shake them off.

Poppy’s bark pulled me out of myself. Tail wagging, stick in mouth, demanding that I throw it for her. I walked past houses where once canaries had been kept in the front window to warn the householders of the dangers of the gas, rising hidden from the vast coal spoil heap which had stood there. The spoil heap was long gone, along with the mines.

Maybe this is where Annabelle meant as I approached a complex of flats towards the ‘top park’. Passing through a kissing gate, I picked up a cinder track on the left, instinctively following it. Then another kissing gate; over a stream and on to a ‘living wall’, from which a host of ferns sprouted, taking this old railway siding wall, another reminder of mining history, into their possession. I threaded my way over rough, rocky ground which hinted at stream bed, though late spring had dried it out.

In front of me was a fence. In front of that. a huge beech which had fallen into oblivion, blocking my way. Poppy darted beneath this carcass, through a small, dog sized, hole in the fence, beckoning me with her loud excited bark, while I struggled to work out how I would clamber my way over this dead sentry. Eventually, I straddled and breeched the trunk and then over the fence which had been denuded of its style by the fallen tree.

I paused long enough for the despair and anger to seep back into my too-full head. It had been such a battle to try to get people to listen to me and my brother. For him, it had become just too much. He could bear the pain no more. I was left behind, trying to respect his choice to let go of life, though I had so desperately wanted him to live.

My eyes adjusted to the dappled light as it trickled through the vivid green beech leaves of late spring. Tiny light pools glinted on the fallen leaves of previous years. My body welcomed the shade, cooling me from the warmth of the day and my physical effort. Tall mature beech trees rose sixty feet or more from the escarpment in search of sunlight, spreading out and contorting their limbs to soak it in, and to feed their hungry young leaves. I exclaimed out loud at this place of magic as I began to take in the splendours of Pit Wood..

The illusion of silence dispersed as I listened closely. Nant Llwynog made her presence felt as she moved gently over the rocks in the stream bed. (I would hear her loud, exultant voice much later when the heavy rains came some months on from this first encounter.) Occasionally the soft breeze would rustle up a barely discernible sound as it blew through the leaves. Sheep called to their young as they grazed on a nearby farm. Then, from the hill above, the ululating call of the curlew, moved through the wood, resonating in the trees, filling my head with wonder, pushing aside despair. I stood, mesmerised, trying to take it all in, exulting in being in this place at this time.

Poppy barked again. Impatient. Desperate to move on. There were more sticks to find, scents to seek. I hesitated, resisting her shout, taking it all in before continuing uphill. And then a pause, arrested by a sudden movement not much above head height. It happened so quickly, and I struggled to recognise what I was seeing. Was this a buzzard flying through the trees? The browns of its plumage certainly suggested this, and I had heard buzzards calling way above the canopy, but this was such a surprise. A good surprise, which prised more space away from my worried head.

As I worked my way to the top of the wood, a short walk, some of the trees changed in character, now stunted by the battering of the winds on exposed ground, forcing me to duck as I made my way beneath their low branches.

And then, as the wood opened out again into open fields and open sky, a red kite jinked on the wind, fine tuning his hover as he eyed up the world beneath for food, mewling as he did so, tempting his pray into the open and pushing aside more worry in my troubled head.

I knew from this first encounter that I would be back to Pits Woods, camera in hand, challenged to capture just a hint of this special place which had cleared my head of troubles, if only for a moment. Those two hours had taught me that I could lose myself in this place, that I could spend the rest of my life getting to know its intimate secrets as it changed with the weather, the seasons and the time of day. I knew too, that this was a place which would bring me solace and refuge when I needed it.

Roy Carr

“…this walk itself was about the colour of the autumn leaves, the scent of a fern, the texture of lichen between my fingers, the feel of rain on my skin. It is just that when I come to reflect on the walk that I have taken that I cannot help but delve further, deeper. This is the person who is walking: I carry all these memories and experiences within me. I may choose to travel empty handed, but I have a stuffed backpack of life that comes with me wherever I may go. Most of the time it is buckled up tight, but as I write it is as though I have chosen to sit on some mossy stump and start to unpack, pulling things out one by one and examining them. And as I turn each thought, each memory between my fingers, I ask myself, what is this thing? What is it doing in my baggage? Why do I carry it with me, always, rather than having just discarded it along the way?”

Neil Ansell from “The Last Wilderness, A Journey Into Silence”

It was not a girly thing to walk through the drifts, but boys were fascinated by the trucks, smell, dirt, noise.

My gang, in Mary street, would have expeditions to the wood and build dens. We would collect fallen branches to add to our bonfire for November 5th – ideal for arsonists. At that time, the tip alongside Bethel, the Pentacostal chapel, extended toward the railway line probably as far as the Post office. It formed a sort of headland because thousands of tons had been excavated and taken away during World War 2. That was the site for the bonfire.

The dens in the woods and tips were normally partly excavations and then covered with branches and any materials we could purloin, legally or ????? The material of conveyor belts were ideal. Pieces would sometime come out of the Drift with the coal and shale. Since there was no distance between there and the wood, it was ideal to sneak it away and then camouflage it.

We were basically feral. We could be out of the house for hours and our parents would have no idea where we were and what we were up to. It was marvellous. Some would say our parents were uncaring and irresponsible. My answer to that is nonsense. BUT we did break every rule in the Health and Safety Handbook currently available. Few adults would trouble us in the Pits Wood. We were either attacking Germans or Indians depending on the film being shown in the Workmen’s Hall. Tarzan films would also stir the imagination. The conveyor belting sometime would be ‘available’ in 1 or 2 ins strips and a long piece of that would be fixed to a branch and the Tarzan call would accompany the wild swing into space.

At the top of the wood is Love Quarry. A lot of stone was excavated for Bedlinog buildings there. It is Pennant Sandstone, sometime blueish when fresh but the iron content rusts to brown. There used to be large crows nesting up there, but few below in the wood.

Some of the village gardeners would dig leaf mould in the wood particularly for prize potted flowers and plants. It was free and did the job peat-based composts do now. It was not unusual to see people carrying a sack of the leaf mould. Some people used it to improve the fertility of soil. Environmentalists would be jumping up and down if they knew.

Carwyn Hughes, 84

More from Roy Carr

Roy’s website

Thank you for visiting, Cynon Valley Museum is not possible without you, please consider making a monthly or one off donation and support your local museum.